As a child growing up in New York, October and November were always a time to celebrate Native Americans and their role in the founding of America. In elementary school, we sang songs about how Christopher Columbus “sailed the ocean blue.” We learned that he met Native Americans in the Caribbean and called them “Indians” because he thought he arrived in India. We learned how Native Americans helped early settlers and concluded the season by dressing up as Pilgrims and Native Americans for Thanksgiving.

I am Latino, Dominican and Puerto Rican more specifically, and most of my friends were Latino, Black, or White. I knew that there were still groups of Native Americans living in America — like the Navajo, Cherokee, or even the Eskimos — but I didn’t know any Native Americans personally. Native Americans were something from the history books. I especially never considered myself to be a Native American. Now, I wonder if I was wrong.

The subject of race and ethnicity were very confusing for me as a child. Like many Latinos from my era, we did not differentiate between race and ethnicity. People were either White, Black, or Latino. If someone asked me what I was, I would reply, “I’m Latino,” or “I’m Hispanic.” It was not uncommon for my friends or biological family to say, “I’m not Black, I’m Dominican,” or “I’m not White, I’m Puerto Rican.”

Latinos could be fair-skinned with red hair and blue eyes, or chocolate skinned with kinky curls.

It is well known that almost all Latinos from the Caribbean Islands are a mix of European and African. This is because in the Caribbean, more so than in mainland America, European colonizers mated with their African slaves and servants prodigiously. Many Caribbean islands also relied on free Blacks and Mulattos (mixed race) to manage plantations. This resulted in an intermediary mixed-race class in the Caribbean, which was absent in mainland America.

The intermixing of races is why it is difficult for Caribbean Latinos to understand America’s racial categories. Almost all Caribbean Latinos are mixed race and categorizing us as White or Black largely relies on the color of our skin, which is a rather superficial characteristic. For many Latinos, the color of their skin can vary greatly between family members or siblings. Even between the seasons, my skin color varies — in the winter I look more like a tanned Spaniard and in the summer I appear more Black.

To make racial matters more complicated, recent DNA testing has revealed that many Caribbean Latinos also have Taíno ancestry.

Taínos are a subcategory of the Arawak people. They were the indigenous people of the Caribbean Islands, also called the West Indies, which includes the islands of the Dominican Republic and Haiti (Hispaniola), Puerto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Cayman, Bahamas, and many others.

Taínos were the first indigenous people that Christopher Columbus met in the New World. They were the people that Columbus mistakenly called “Indians” and in his journal he wrote about them that, “They were very well built, with very handsome bodies and very good faces… They should be good servants.”

Later, Columbus and his men shipped 500 Taínos to Spain to be sold into slavery — 200 died on the journey. When he returned to the island a few years later, he ordered every Taíno to bring him gold, and those that didn’t had their hands chopped off. In the decades that followed, the Taíno people were wiped out by disease, slavery, and genocide.

I always thought that the indigenous people of the Caribbean Islands were extinct. I never even heard the name “Taíno” until I was an adult. In the early 2000s, I learned about the movement to rename Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples Day. This inspired me to learn more about the indigenous people of Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. To my surprise, I learned that there were an estimated 3 million Taínos living in the Caribbean before Columbus arrived. Their language gave us words like can canoe, hammock, barbecue, tobacco, and hurricane. They were peaceful and generous people, which unfortunately allowed Columbus and other colonists to exploit them.

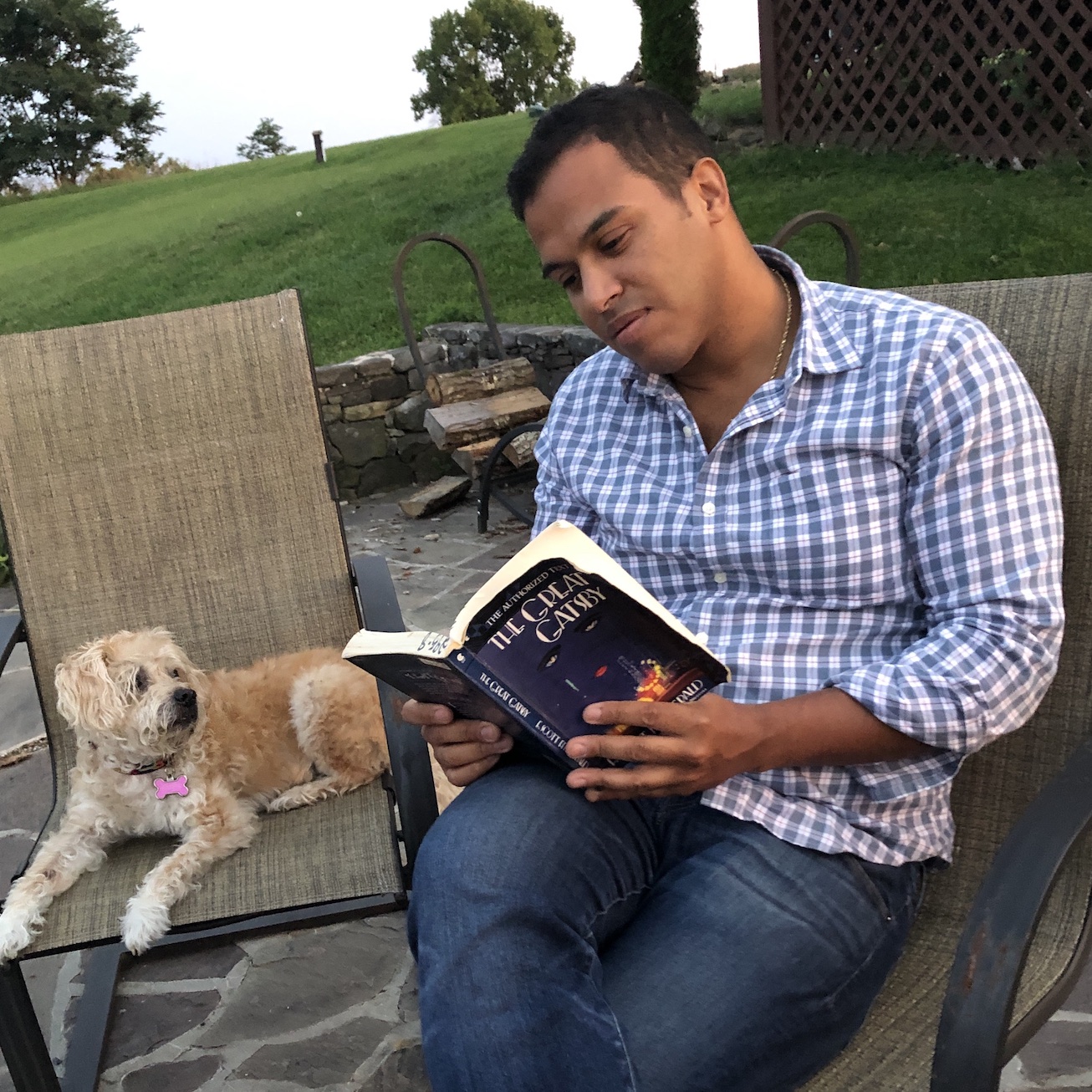

When my daughter was born, I wrote a bilingual children’s book for her so that I could teach her about the Taíno people. The book is called “Zandunga: The Taíno Warrior” and features different aspects of pre-colonial Taíno culture, lifestyles, and themes.

I learned a lot about the Taíno people while writing the book, but after I wrote it, I had a nagging question… “Was I Taíno?”

While researching the book, I learned that some Caribbean Islanders still had Taíno ancestry, but none of my family could trace our history back that far. So, I took a DNA test, and the results were surprising. I was expecting to have 1% or 2% Taíno DNA. To my surprise, my DNA was 13% Taíno or about 1/8th (I was also 50% Spanish from Andalusia and 30% West African, mostly from Senegal, Guinea, Nigeria).

I was Taíno!

Further research revealed that I may not be alone. For most of modern history, the Taíno’s were thought to be extinct, but recent studies have shown that that may be incorrect.

Although there are no surviving Taíno tribes, genome studies have shown that up to 61% or Puerto Ricans, 30% of Dominicans, and 33% or Cubans have Taíno DNA. World-wide, Latinos from these three countries number about 23 million (9 million Puerto Ricans, 11 million Dominicans, and 13 million Cubans).

If the DNA studies are accurate, then there may be over 13 million Taíno decedents living around the world, and many more if you look at the other West Indian Islands. Not only are Taínos not extinct, but they may be one of the largest groups of indigenous decedents outside of Central or South America.

This led me to another question, “Why don’t we celebrate Taínos when we celebrate Native American history?”

For example, I recently visited the Heard Museum in Phoenix, one of the nation’s premier Native American art and history museums. I could not find a single reference to Taíno people in the Museum. Similarly, you would be challenged to find a Taíno exhibition at most Native American festivals around the country. It’s as if the Taíno people were forgotten.

I tried to understand why Taínos were forgotten in Native American history, but I realized that I wasn’t even sure if Taínos were Native Americans.

I asked my Dominican friend, “Are Taínos Native Americans?”

She thought for a few minutes and then responded, “I guess it depends on what you consider Native American. Yes, they are indigenous, but they’re not Native Americans like ‘Native Americans’ in the U.S.”

“What about Puerto Rico?” I replied, “That is part of the U.S.”

“I guess that is part of the U.S.” she said perplexed, “I’m not sure.”

I wasn’t sure either.

Of course, Taínos were indigenous people, but I wasn’t clear if the term Native American refers to indigenous people from the 50 United States only, or if Native American refers to indigenous people from all of North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean.

As it turns out, there is not a clear definition of what Native American means. Some organizations define Native American as the indigenous people of the United States (not including its territories), others expand the definition to include the United States and its territories (Puerto Rico and Guam included), and others define Native Americans as any indigenous people from the Western Hemisphere. If we define Native Americans as indigenous people from only the 50 United States, then Taínos would not be considered Native Americans. However, if we include the U.S. territories or greater Americas, then Taínos would be included as Native Americans.

Although the definition of Native American is not universally agreed upon, we should include Taínos as Native Americans for two important reasons.

The first reason why we should include Taínos in Native American history is that the term Native American and American Indians have historically been used interchangeably. Remember that Taínos were the first indigenous people to ever be called Indians. They played a pivotal role, although tragic, in the arrival of Christopher Columbus and the early history of the New World. We should not exclude this important group of indigenous people when remembering Native American history.

The second reason why we should celebrate Taíno heritage is that Taíno decedents are foundational to the United States. Not only is Puerto Rico (one of the ancestral homes of Taínos) a commonwealth of the United States, but Taíno decedents also constitute a large population of U.S. Citizens. If the DNA studies are correct, then there may be over 4 million Latinos with Taíno ancestry living in the United States. When the United States celebrates Indigenous People Day in October and Native American Heritage Month each November, we should also celebrate Taíno heritage.

Taíno heritage is American heritage.

Ultimately though, Merriam-Webster says that a Native American is, “a member of any of the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere especially: a Native American of North America and especially the U.S. — compare American Indian.”

Based upon this definition, and the previous reasons discussed, Taínos are Native Americans. The Caribbean is part of North America and Puerto Rico is part of the U.S.

The definition of Native American can be confusing, which is one reason why Taínos are often forgotten in Native American celebrations. Another reason is because our culture, language, and heritage are largely extinct. Although a few words, artifacts, and old anthropology journals exist, we know very little about the Taíno people. Although there are millions of Taíno decedents, our culture was mostly wiped out by colonizers and missionaries. In contrast, tribes like the Navajo, Hopi, and Cherokee still practice tribal rituals that have been passed down through generations.

Fortunately, there are new efforts afoot to restore Taíno culture and heritage. Various groups, influencers, and authors are attempting to recreate Taíno language, culture, and customs from various historical artifacts and old journals. Thanks to the internet, we are experiencing the early stages of a Taíno culture revival.

Another reason why Taínos have historically not been celebrated with Native American heritage is because most Caribbean Latinos and West Indian islanders do not know their own ancestry. Like myself, most of us were taught that the Taíno were extinct. Only recently, within the past two decades, has DNA testing allowed us to learn that Taíno genealogy is more widespread than many historians or anthropologist believed. As more and more people explore their own DNA through websites like 23andMe or Ancestry.com, I suspect that more and more Latinos and West Indians will take interest in their own Taíno ancestry.

Taínos played an important role in the history of America. They were the first indigenous people that Christopher Columbus encountered and were pivotal in the founding of the New World. Although our ancestral culture and traditions are extinct, our blood continues to live on. Today, Taíno decendents make up a large population of the United States and the world. Large percentages of Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Haitians, Jamaicans, and other West Indians have some Taíno DNA. Their legacy continues to live on and when we celebrate Native American heritage, we should also celebrate the incredible Taíno people.

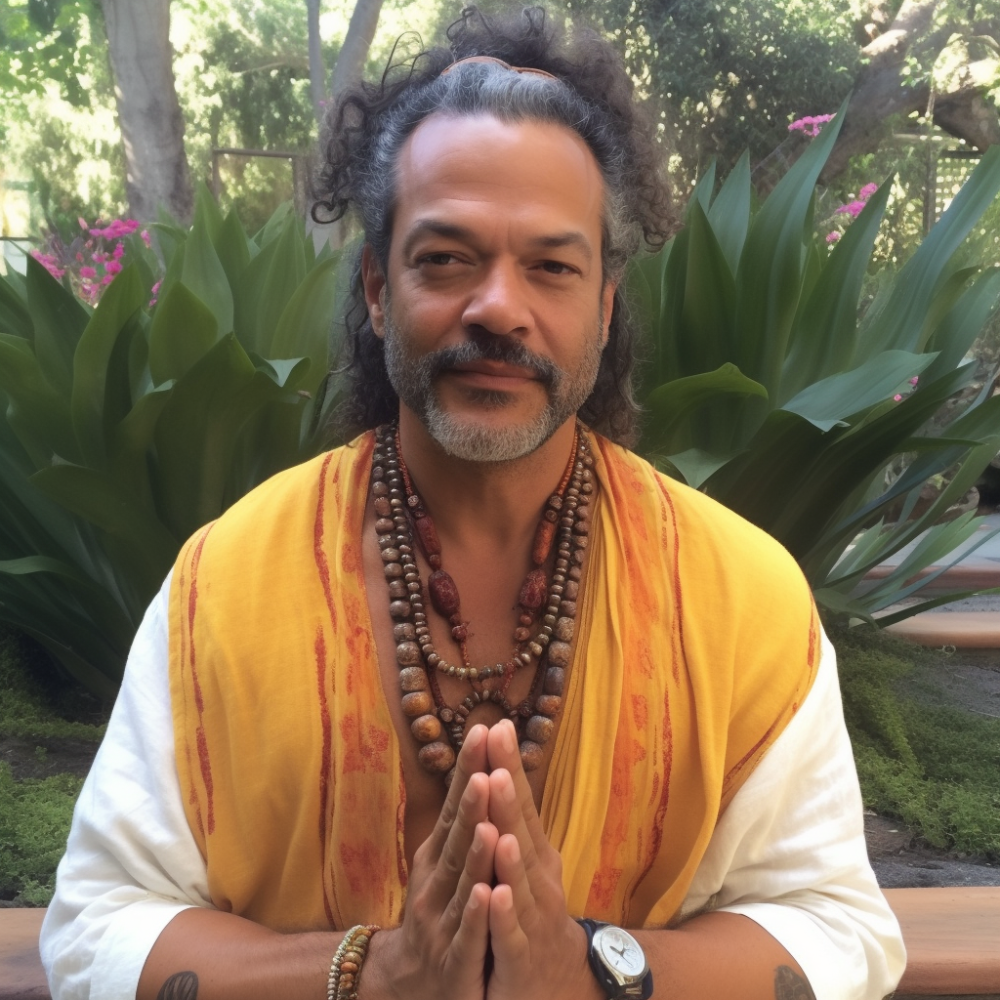

I hope you enjoyed this article! Please clap, like, and re-share. Thank you so much! Your support is greatly appreciated. Sincerely — Robert Solano.

Check out my children’s book “Zandunga: The Taino Warrior.” Get your copy now on Amazon.

—stories, insights, and perspectives from my journey.

Ready to Explore Plant Medicines?

DON’T START YOUR JOURNEY WITHOUT THIS GUIDE

Download the free Psychedelic Transformation Framework™ Guide and discover the proven framework that ensures safe, breakthrough experiences for leaders who are ready to discover their awakened self.